The Norwegian Education Mirror, 2019

Innhold

About The Education Mirror

The Education Mirror is the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training’s annual publication with insights such as statistics and analysis about kindergartens, primary and secondary education in Norway. The publication tracks the pupils’ entire educational trajectory from kindergarten to upper secondary education or training.

The directorate publishes updated statistics and research throughout the year. In The Education Mirror, we seek to tie up the loose ends and provide a summary of key trends from the academic year, and this edition is for 2018–19. The Education Mirror is also a gateway for those looking to obtain additional figures and read extended research articles.

The target audiences for this publication, are those who are involved in policy design for the kindergarten and education sectors and others who may be interested in the subject matter.

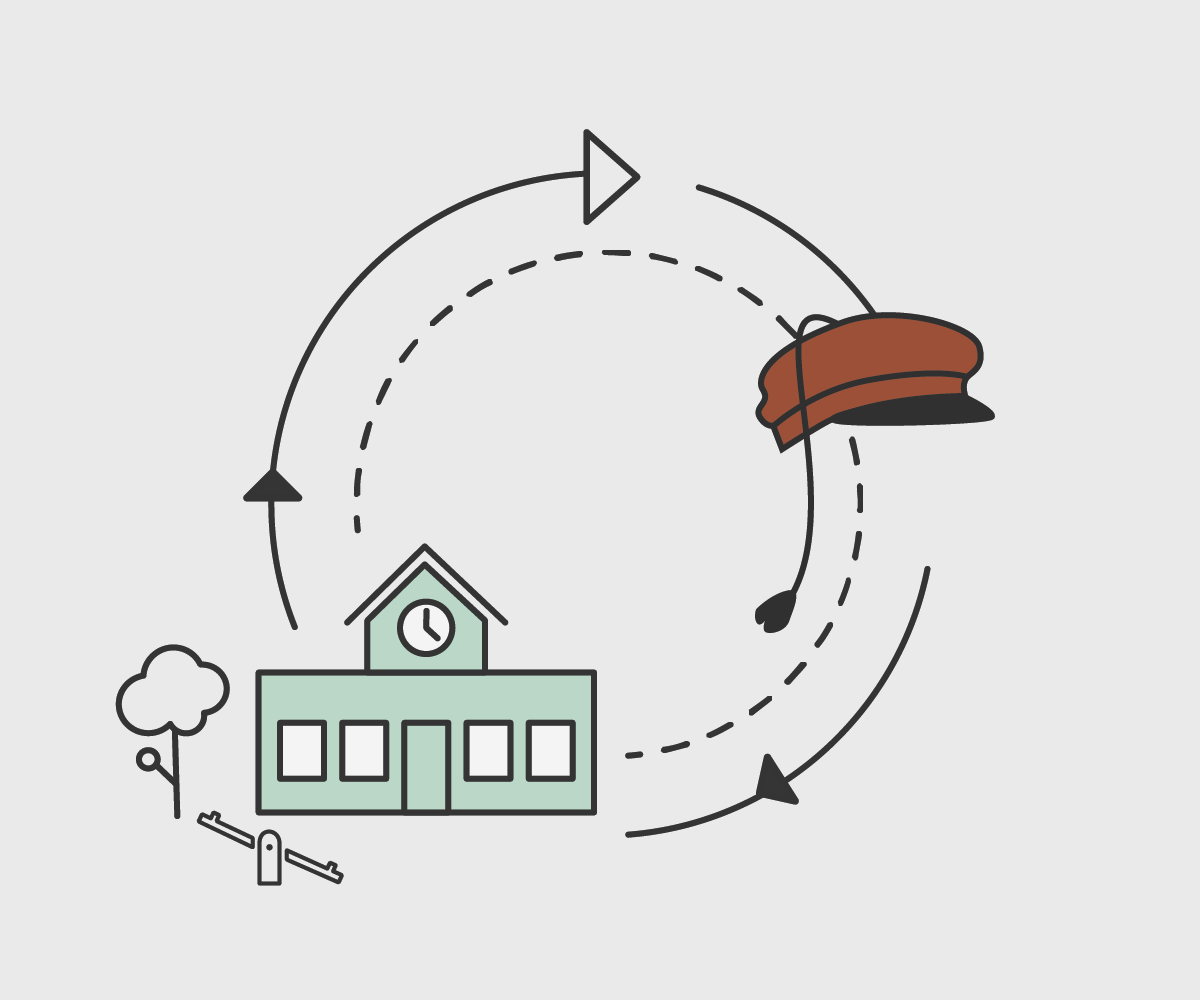

In this version, we take an extra look at how immigrants and their descendants fare in the education system. How do we ensure that financial circumstances do not prevent enrolment in kindergarten and out-of-school-hours care, and what differences are there in learning outcomes and completion rates between pupils with an immigrant background and other pupils? Figures show that young people who arrive in Norway towards the end of compulsory education, face additional challenges in terms of completing their education and that apprentices with immigrant backgrounds struggle more than other young people to find apprenticeships.

Kindergartens

Kindergarten enrolment has increased considerably in recent times. 9 out of 10 children in Norway now attend kindergarten. Although kindergarten is not compulsory, it is seen as a part of the Norwegian education system. Kindergarten is an important arena for children's all-round development through care, play and learning.

Number and types of kindergartens

There are 5,788 kindergartens in Norway. Among these, 498 are family kindergartens and 117 are open kindergartens. 47 per cent of kindergartens are municipal kindergartens, while 53 per cent are privately owned. 50 per cent of children attend municipal kindergartens. Local authorities cover more than 80 per cent of the cost of running both municipal and private kindergartens. Around 15 per cent of the cost is met by the parents, while earmarked government funding and other grants from local authorities and kindergarten owners make up a small part of the kindergarten funding.

16 per cent of children attend kindergartens with more than 100 children

The number of kindergartens has fallen steadily in the last few years. Kindergartens with fewer than 26 children are seeing the greatest decline. The number of very large kindergartens has stabilised in recent years. Around 16 per cent of children attend kindergartens with more than 100 children. This figure has remained stable in the past five years.

Children in kindergarten

Kindergarten enrolment has increased considerably since the 1980s. In 1963 only 2 per cent of children aged 1–5 attended kindergarten (Statistics Norway). The increase in enrolment is due both to changes in society, such as rising labour force participation amongst women, and to various political initiatives. Following the Kindergarten Agreement in 2003 – when the Norwegian parliament voted to establish kindergarten provision for every child in law – there has been a significant increase in the number of children who attend kindergarten. The biggest increase in enrolment has been amongst the youngest children and amongst minority language children.

High enrolment rates, especially amongst the oldest children

At the end of 2018, 278,578 children were enrolled in kindergarten. A total of 91.7 per cent of children in the 1–5 age group are enrolled in kindergarten. However, the proportion of children who are enrolled in kindergarten increases with age. 73.2 per cent of 1-year-olds attend kindergarten, while for 5-year-olds the enrolment is 97.6 per cent.

| All age groups | Number of children | Enrolment rate |

|---|---|---|

| 0 years | 2196 | 4.0 |

| 1 years | 42150 | 73.2 |

| 2 years | 56264 | 93.2 |

| 3 years | 58436 | 96.4 |

| 4 years | 59303 | 97.3 |

| 5 years | 59836 | 97.6 |

| 6 years | 393 |

93 per cent of children aged 1–5 attend kindergarten. For 1-year-olds the figure is 73 per cent.

Staff

Kindergartens employed 77,100 FTEs in 2018. 64,100 of these FTEs are pedagogical leaders and other staff who work directly with the children. Staff who work directly with the children are referred to as contact staff/ core staff. In addition to these come kindergarten heads, special educational needs staff and staff providing accelerated language learning. 3,200 FTES are filled by admin staff, caretakers, cleaners and cooks.

4 out of 10 kindergarten staff are teachers

41 per cent of core staff are qualified kindergarten teachers or hold equivalent qualifications. 20 per cent are qualified child care and youth workers.

The proportion of staff with a kindergarten teaching qualification or equivalent rose from 38.0 per cent in 2016 to 41.0 per cent in 2018.

Improved staff density

Staffing levels nationally remained largely unchanged at 6.0 children for every staff member between 2013 and 2017. In 2018 staffing levels increased to 5.8 children for every staff member. There has been a corresponding reduction in the number of children per kindergarten teacher or equivalent since 2016.

Municipal kindergartens have higher staff density than private kindergartens. Municipal kindergartens have an average of 5.7 children for every staff member, while private kindergartens have an average of 6.0 children for every staff member. It appears that new and stricter regulations are resulting in a gradual increase in staff and teacher density.

More dispensations

The new regulations on teaching staff has led to a need for significantly more pedagogical leaders. Some of the kindergartens that are unable to achieve the required ratio apply for dispensation. In 2018 a total of 10 per cent of FTEs worked by pedagogical leaders were permanent or temporary dispensations from the qualification requirement, an increase of 5 percentage points compared to 2017. Before 2018 there was a dwindling number of pedagogical leaders with dispensation from the qualification requirement, but since the requirement to the teacher-to-child ratio was changed in 2018 the percentage of pedagogical leaders with dispensations has increased once again. It would therefore appear that imposing stricter requirements – at least during a transition period – may result in an increase in the number of dispensations.

4 in 10 kindergarten staff are kindergarten teachers.

There is an average of six children for every staff member.

Kindergartens with dispensation from the child-to-teacher ratio

| Indicator | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dispensation from the teacher-to-child ratio | 121 | 108 | 407 |

| Percentage | 2 % | 2 % | 8 % |

| All kindergartens | 5288 | 5226 | 5173 |

Stricter requirements result in genuine improvements

Since 2016 the number of children per teacher has fallen from 16.1 to 14.4, while the number of children per core staff member has fallen from 6.0 to 5.8. At the same time many kindergartens are also granted dispensation from the child-to-teacher ratio. The local authority may grant a dispensation from the child-to-teacher ratio for up to one year at a time if there in particular reasons. There is reason to believe that the proportion of kindergartens with a dispensation or the proportion of kindergartens not meeting the new requirements could continue to fall over time, as happened in the years before the child-to-teacher ratio was lowered.

Kindergarten quality and content

The staffing requirements are founded on the belief that staff density and staff qualifications are linked to the quality of the kindergarten provision. Studies show that staff numbers and formal staff qualifications both have an impact on the children’s well-being and development in that they affect the interaction between children and staff (OECD, 2018). Class size and the number of children per staff member also impact the quality of the interaction between the children and kindergarten staff (OECD, 2018).

Observations of kindergarten practices have revealed that kindergarten teachers are more likely than other staff members to actively set boundaries and enable verbal communication and autonomy for the children when interacting with them (Bjørnestad et al., 2019). A study of the youngest kindergarten children (GoBaN) found that qualified staff, high staff density and small and stable classes have a positive effect on the adult-child relationship, which in turn positively impacts the children’s well-being (Bjørnestad & Os, 2018).

Staff want additional training

Kindergarten employees are reporting a growing need for additional skills in relation to children entitled to special educational support and children with a mother tongue other than Norwegian. This is particularly true for staff with a high proportion of such children in their kindergarten (OECD, 2019).

The desire for further training amongst both kindergarten staff and owners is being met by offering in-service training, amongst other things. 367 kindergarten heads enrolled in in-service training in the 2019-20 academic year. The head teacher training course is a management training programme for kindergarten heads. In the same academic year 900 kindergarten teachers were offered continuing education by the Directorate for Education and Training. The training covers the learning environment and pedagogical leadership, science and mathematics, and language development and language learning.

One barrier against participating in such skills development programmes is that kindergartens lack replacement staff to cover any absences, according to the TALIS kindergarten survey. Another barrier is lack of time due to family commitments (OECD, 2019).

Kindergartens are increasingly engaging with the Framework Plan

Kindergarten content is regulated by the Kindergarten Act and the Framework Plan for the Content and Tasks of Kindergartens. The Framework Plan defines values, responsibilities and roles, working methods and learning areas, amongst other things.

The Directorate for Education and Training's annual survey of the kindergarten sector found that kindergartens have stepped up their work on all of the learning areas (Fagerholt et al., 2019). This can be interpreted as a growing emphasis on kindergarten content. 73 per cent of the owners who were surveyed said their head teachers have welcomed the new Framework Plan. The topics in the Framework Plan with the greatest need for support materials in 2018 were digital practices, life skills, health and sustainable development (Fagerholt et al., 2019).

Parents are satisfied with their children’s kindergarten

Parents who responded to the survey are generally satisfied with the kindergarten provision. 93 per cent of parents who responded to the survey are very or fairly satisfied with the provision on the whole. The parents’ responses have changed little in the three years the survey has been running. The Parent Survey shows that parents are the most satisfied with the children’s well-being and development and the relationship between the children and the adults. As many as 97 per cent of parents completely or partially agree that their child enjoys going to kindergarten.

However, there is a slight fall in satisfaction ratings when it comes to staff density in 2018 compared with 2017 and 2016. This may be due to the attention around the new core staff ratio. Actual staff density increased in the same period. There also seems to be little or no correlation between the structural characteristics of a kindergarten – such as its size, staff qualifications and staff density – and parent satisfaction (Opinion, 2019).

The parents of the youngest children are slightly more satisfied with the kindergarten provision than the parents of the oldest children, although the difference is minor. When asked about overall satisfaction, 95 per cent of parents with children aged 1–2 and 92 per cent of parents with children aged 3 or older said that they are very or fairly satisfied with their kindergarten. The parents of the youngest children are slightly more satisfied with the staff density than the parents of the oldest children, 77 per cent and 71 per cent respectively. This may be because there are stricter staffing requirements for children under the age of 3.

9 in 10 parents are satisfied with their kindergarten

An inclusive kindergarten policy

Kindergartens are part of the education system, and it is a political goal for all children to be able to attend kindergarten. A number of studies have found that children who have attended kindergarten have better language development and do better at school than children who have not attended kindergarten. Some studies show that this does not simply imply that children who would have done well at school anyway have also attended kindergarten but that attending kindergarten does in itself have a beneficial impact on children’s linguistic and social development. This is particularly true for children from families with limited education and low incomes (Mogstad & Rege 2009; Havnes & Mogstad 2011).

Children from families where the parents have limited education and low incomes and parents from minority backgrounds are less likely than other children to attend kindergarten (Moafi 2017). These background characteristics will in many cases overlap. A raft of measures have been taken in recent years with a view to increase enrolment amongst these children. The measures are particularly linked to financial barriers.

Kindergarten can have a positive impact on children’s language development

A summary of knowledge on language learning in kindergartens with multilingual children has found that exposure to the second language is important to the children’s language development. Exposure can take place in kindergarten, and research shows that kindergarten teachers should use methods that engage the children in order for them to learn. The make-up of the group of children and how the activities are executed are important (Lillejord et al., 2017).

The effect of kindergarten on language development is thus dependent on both enrolment in kindergarten and on the quality of the interaction between children and staff and between the children. Belonging to a linguistically competent group of children can compensate for differences in the parents’ education levels and help equalise the language skills of kindergarten children (Ribeiro et al., 2017).

The evaluation of a trial with free core time in kindergartens in the Oslo districts of Grorud, Alna, Stovner and Bjerke found that pupils who had been offered free core time performed better in the national reading test in Year 5 and that fewer of them were granted an exemption from the test (Drange, 2018). Children from immigrant backgrounds in districts that offer free core time perform on average as well as children generally in districts without such provision in national tests in Year 5. The good results in the reading test suggest that the offer of free kindergarten time leads to an improvement in the children’s language skills. This is in line with the objective of the initiative, although it is difficult to draw any definitive conclusions on the causal effects (Drange, 2018).

More minority language children attend kindergarten

There were 50,900 minority language children enrolled in kindergarten in 2018, an increase of almost 10,000 on five years ago. There has been a steady increase in minority language children attending kindergarten in all age groups. The increase is primarily due to a growing immigrant population, but there has also been an increase in the overall enrolment rate amongst minority language children.

83 per cent of minority language children were enrolled in kindergarten in 2018 (Statistics Norway), an increase of 4 percentage points on 2014. The greatest disparity between minority language children and other children can be seen amongst 1-year-olds. The gap has been decreasing gradually since 2006. 2 in 10 minority language children who attend kindergarten receive accelerated Norwegian language tuition which requires additional staff resources.

Kindergarten can have a positive impact on language development in minority language children.

18 per cent of children enrolled in kindergarten are minority language children, but there are significant variations between different municipalities and urban districts. Minority language children constitute the highest percentage of the enrolled children in Drammen and Oslo where 35 and 30 per cent respectively of the enrolled children are minority language children.

Discount schemes are working

The purpose of the national discount schemes is to boost enrolment and to improve the circumstances of financially challenged families.

A total of 33,459 low-income households received a reduction in parent contributions in 2018. A total of 41,900 children have benefited from reduced kindergarten fees and 26,000 children from free core time due to low income.

Local authorities spent more than NOK 644 million on reducing parent contributions due to low household income in 2018. This is NOK 146 million more than in 2017.The national discount scheme for reduced parent contributions has helped increase kindergarten enrolment amongst the households in question by 1.2 per cent. The discount scheme has also cut the cost of a full-time kindergarten place for the households in question and has consequently helped reduce poverty (Østbakken, 2019).

Not everyone who is entitled to a discount receives it

In 2017, 61 per cent of those entitled to free core time received it. This is an increase on 2015, when only 45 per cent of those entitled to free core time received it (Østbakken, 2019).There has also been an increase in parents being granted reduced parent contributions under the 6 per cent rule.

Although the proportion of children who are entitled to a discount and receive it is increasing, a large percentage still do not claim their entitlement. Reasons for this could be that they are not aware of the schemes and the fact that families need to actively apply and produce documentation. A complicated application procedure could therefore mean that many of those who are entitled to a discount do not receive it. The government has therefore put forward a proposal to simplify the application process.

Some parents may have other reasons than cost for not sending their children to kindergarten. This could include their views on what is in the best interest of their children, a desire to look after their young children themselves and a preference for other childcare arrangements (Trætteberg and Lidén 2018). Kindergarten enrolment is lower amongst children with non-working mothers than amongst children with working mothers. If one parent is not in work, there is less of a need and desire for childcare and probably less money to spend on kindergarten fees.

There may also be other kindergarten-related expenses on top of the parent contribution that prevent enrolment, such as the cost of meals, transport and equipment. Kindergartens may charge for the cost of meals on top of the maximum fee. The discount schemes do not cover meal costs. There are significant differences in meal costs from kindergarten to kindergarten, with some kindergartens not charging for meals at all and others charging more than NOK 1,000 per month.

Four in five parents of 1 to 5-year-olds who do not apply for a kindergarten place for their child say it is because “it is important for the child to stay with the mother in the early years”. Seven in ten parents who receive cash-for-care benefit say that they would not apply for a kindergarten place if the benefit was withdrawn (Moafi 2017). These may be indications that there are factors other than financial circumstances that impact kindergarten enrolment rates.

Many people may find the process of applying for a discount complicated.

Sources

Bjørnestad, E. & Os, E. (2018). Quality in Norwegian Childcare for toddlers using ITERS-R. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal. 26(1): 111-127.

Drange, N. (2018). Gratis kjernetid i barnehage i Oslo. Rapport 2: Oppfølging av barna på femte trinn. Statistisk sentralbyrå. Rapport 2018/34.

Fagerholt, R. A., Myhr, A., Stene, M., Haugset A. S., Sivertsen H., Carlsson E. & Nilsen, B. T. (2019). Spørsmål til Barnehage-Norge 2018. Analyse og resultater fra Utdanningsdirektoratets spørreundersøkelse til barnehagesektoren. TFoU-rapport 2019:2.

Havnes, T & Mogstad, M. (2011). No child left behind: Subsidized child care and children’s long-run outcomes. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 3(2): 97-129.

Lillejord S, Johansson L Canrinus E, Ruud E & Børte K. (2017). Kunnskapsbasert språkarbeid i barnehager med flerspråklige barn – en systematisk forskningskartlegging. Oslo: Kunnskapssenter for utdanning.

Mogstad, M & Rege, M. (2009). Tidlig læring og sosial mobilitet: Norske barns muligheter til å lykkes i utdanningsløpet og arbeidslivet. Samfunnsøkonomien.nr 5: 4-22.

Moafi, H. (2017). Barnetilsynsundersøkelsen 2016. En kartlegging av barnehage og andre tilsynsordninger for barn i Norge. SSB rapport 2017/35.

OECD. (2019). Providing quality Early Childhood Education and Care. Results from the Starting Strong Survey 2018. Paris: TALIS, OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2018). Structural characteristics and process quality in early childhood education and care: A literature review. OECD Education Working Paper No 176.

Opinion. (2018). Frafallsanalyse. Gjennomført for Utdanningsdirektoratet. Oslo: Opinion AS.

Ribeiro, L. A., Zachrisson H. D. & Dearing, E. (2017). Peer effects on the development of language skills in Norwegian childcare centers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 41, 1-12.

Trætteberg, H & Lidén, H. 2018. Evaluering av moderasjonsordningene for barnehagen: Delrapport 1. Rapport – Institutt for samfunnsforskning 2018:4.

Zachrisen, B. (2017). Kultursensitiv omsorg i barnehagen. Barn: Forskning om barn og ungdom i Norden. 2017 (2-3), 105-119.

Østbakken, K.M. (2019). Evaluering av moderasjonsordningene for barnehagen. Delrapport 2. Institutt for Samfunnsforskning. Rapport 2019:10.

Compulsory education

The compulsory education in Norway is 10 years, and each year over 60,000 children start school. There is a tendency towards fewer and larger schools, although due to demographic factors, there is still a large number of small schools. As a result of the teacher-to-child ratio and increased funding, the number of children per teacher has fallen in recent years, especially in the lower year groups.

A large proportion of pupils are enrolled in out-of-school-hours care, especially in the first two years of school. High enrolment rates have resulted in increased attention around content and inclusion in out-of-school-hours care.

There has been an increase in the number of adults enrolling in primary and lower secondary education, almost all of them minority language speakers.

Pupils in compulsory education have seen their grades improve in recent years. Girls receive slightly better grades than boys after Year 10. Boys outperform girls in numeracy and English, and in autumn 2019 they performed as well as girls in the Year 5 national reading test for the first time. In the case of 15-year-olds, however, PISA 2018 shows that boys have poorer reading skills than girls.

18 per cent of pupils in compulsory education have an immigrant background, a number more than double the figure in 2004. Pupils from immigrant backgrounds generally do well in the Norwegian education system, although they receive slightly lower grades than other pupils. Many pupils who arrive in Norway near the end of compulsory education are not awarded an average point score when they complete lower secondary.

Number of pupils and schools

In the 2019-20 academic year there were 636,250 pupils enrolled in public and private primary and lower secondary schools in Norway.

The pupil numbers have remained fairly stable nationally in the past decade, but there are significant differences between countie: Pupil numbers in Oslo have increased by 23 per cent in the past ten years, in Akershus county by 12 per cent, whilst there was a decline of 15 per cent in Finnmark and 11 per cent in Nordland in the same period.

Pupil numbers will fall by 4 per cent by 2028

Changes in pupil numbers can be highly significant when local authorities are planning school structures and teacher demand. Statistics Norway expects the number of pupils of primary and lower secondary school age to fall to 613,000 by 2028, which is a drop of 4 per cent on today’s figure. From 2023 it will fall by a few thousand every year (Statistics Norway, 2016a).

According to these forecasts, Sogn og Fjordane, Finnmark and Troms counties will see the biggest drops in pupil numbers, while Vest-Agder and Akershus will see the smallest decline.

The reason why Statistics Norway is expecting a fall in numbers is that immigration levels are projected to be lower in the coming years. Birth rates have also fallen, and are expected to remain low. There will always be uncertainties surrounding such forecasts.

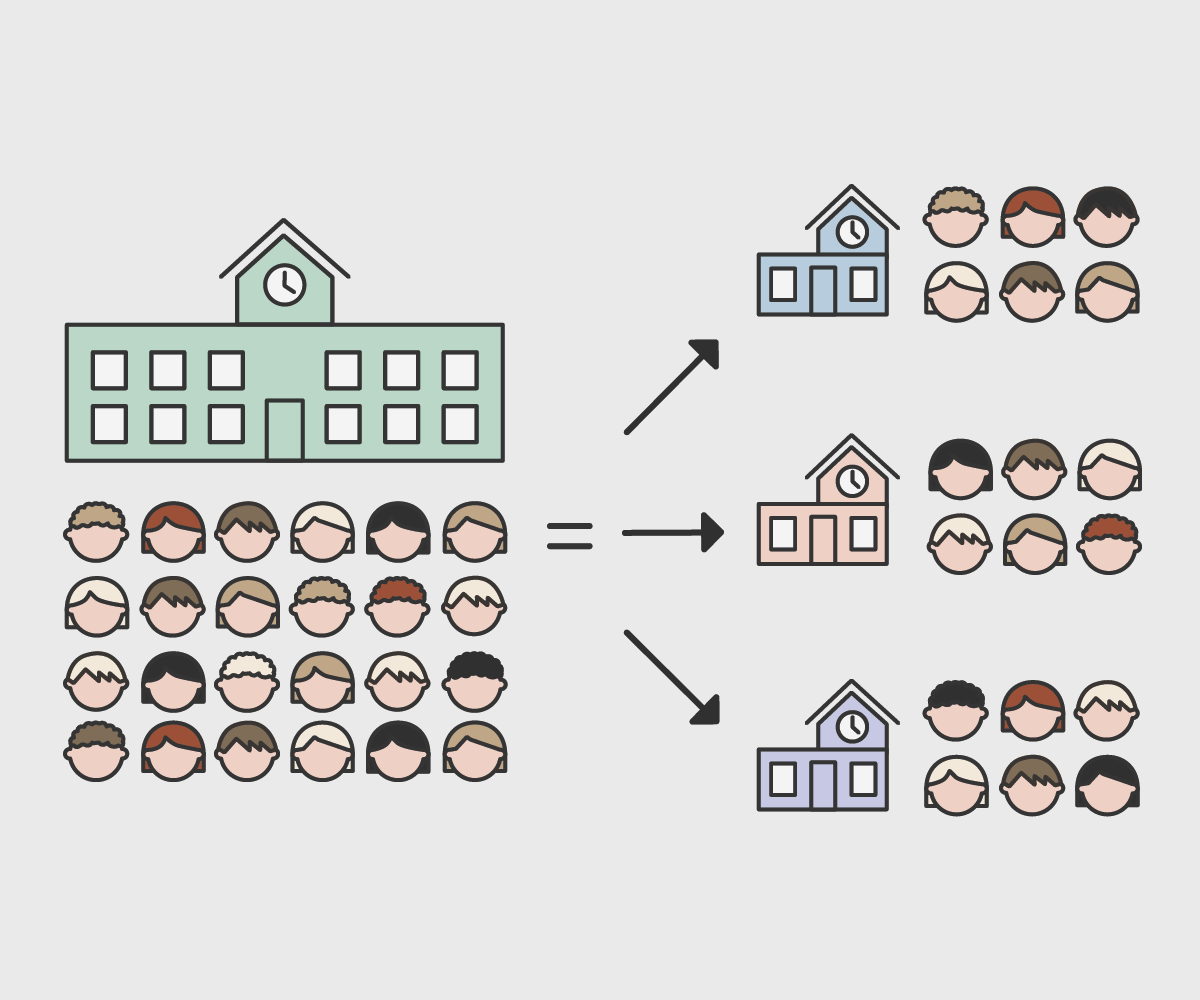

Fewer and larger primary and lower secondary schools

There are a total of 2,799 primary and lower secondary schools in Norway in the 2019-20 academic year. This number is 269 fewer than ten years ago. There is a tendency towards fewer and larger schools in Norway. In the 2019-20 academic year the average number of pupils per school was 227, which is 26 more than a decade ago. 195 schools have 500 or more pupils, which is 72 more schools than ten years ago.

While the number of very large schools is increasing, the smallest schools are dwindling in numbers. In 2009, there were 1,028 schools with fewer than 100 pupils. Today, the figure is 792. 28 per cent of schools have fewer than 100 pupils, but only 6 per cent of pupils attend the smallest schools.

School sizes vary greatly from county to county.

- In Finnmark, Nordland and Sogn og Fjordane at least half of all schools have fewer than 100 pupils.

- In Oslo 39 per cent of schools have 500 or more pupils, an increase of 26 per cent on 2009.

- None of the schools in Finnmark has more than 500 pupils.

An average of 54 schools have closed down, and an average of 27 schools have opened every year since 2009-10. Most of the schools that close down are small, with an average of 69 pupils in the last year they remained open. Low pupil numbers and local authority finances may be amongst the reasons why a school shuts down.

More private primary and lower secondary schools

27,027 pupils are enrolled in private primary and lower secondary schools in Norway in the 2019-20 academic year, a total of 4 per cent of all pupils. There are 261 private primary and lower secondary schools, 99 more than in 2009-10.

Private primary and lower secondary schools are smaller on average than their public equivalents. Private schools had 104 pupils on average in 2019-20, while the average for municipal schools was 241 pupils.

In addition to private primary and lower secondary schools within Norway, there are also nine Norwegian private schools abroad with a total of 765 pupils.

Most schools in the northernmost counties have fewer than 100 pupils. In Oslo it is common for schools to have more than 500 pupils.

Only 1 in 10 public schools that close down is replaced by a private school

Many more public schools are closing down than there are new private schools opening. In only 12 per cent of cases where a public school closes down is a new private school opened in the same location in the same year. Yet 2 in 10 new private schools open in the same location as a closed down public school. Most of these are Montessori schools. 5 per cent of the public schools that shut their doors are replaced by a Montessori school in the same year.

When considering applications to set up new private schools emphasis is placed on the impact of a new independent school on the public school structure. The host municipality’s views are also taken into account.

Diversity in schools

Diversity in schools is increasing. In 2019 a total of 18 per cent of children of compulsory school age came from an immigrant background. Just over half of these children were born in Norway (Statistics Norway). This percentage has more than doubled since 2004.

6 per cent of pupils received special Norwegian language tuition in the 2018-19 academic year. The overall picture is that pupils from immigrant backgrounds are doing well in the Norwegian education system. Yet pupils from immigrant backgrounds obtain slightly lower grades in lower secondary school and are less likely to complete upper secondary.

Almost 1 in 5 pupils in compulsory education has an immigrant background.

Pupils with an immigrant background obtain slightly lower grades than other pupils

Pupils from immigrant backgrounds – that is, pupils who have themselves immigrated to Norway or who were born here by parents who have immigrated – obtain lower average point scores than other pupils. There is a relatively big discrepancy between pupils who have themselves immigrated and pupils born in Norway to immigrant parents.

Pupils who immigrated to Norway from Africa or Asia obtain a 6.7 lower average point score than pupils from a non-immigrant background.

6 percent of pupils are receiving special Norwegian language tuition

Special Norwegian language tuition is provided in the form of accelerated Norwegian language lessons. The tuition may be provided either in accordance with the Curriculum for Basic Norwegian for Language Minorities or by adapting the ordinary curriculum.

The proportion of pupils receiving special Norwegian language tuition is greatest in the early years of compulsory education. 8 per cent of pupils in Years 1–4 received special Norwegian language tuition in autumn 2018, while the figure for Years 8–10 was 5 per cent. There are considerable variations from municipality to municipality in terms of the proportion of pupils receiving special Norwegian language tuition. Amongst the biggest municipalities, Oslo has the highest percentage of pupils receiving special Norwegian language tuition at 20 per cent. The figure in Drammen is also high at 13 per cent.

There are considerable variations from municipality to municipality in terms of the proportion of pupils receiving special Norwegian language tuition. Amongst the biggest municipalities, Oslo has the highest percentage of pupils receiving special Norwegian language tuition at 20 per cent. The figure in Drammen is also high at 13 per cent.

The right to special language tuition

Pupils with a mother tongue other than Norwegian or Sami are entitled to special Norwegian tuition until such time as they are sufficiently fluent in Norwegian to be able to follow ordinary tuition.

7 per cent of pupils receive special Norwegian language tuition.

Sources

Caspersen, J., Buland, S, Valenta, M. & Tøssebro, J. (2019). Inkludering på alvor? Delrapport 1 fra evalueringen av modellutprøvingen Inkludering på alvor. Trondheim: NTNU.

OECD. (2019). Trends Shaping Education 2019. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Statistisk sentralbyrå. (2019). Nasjonale prøver: Foreldrenes utdanning spiller stor rolle. Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå.

Rogde, K., Federici, R. A., Vaagland, K & Wollscheid, S. (2018). Spørsmål til skole-Norge. Analyser og resultater fra Utdanningsdirektoratets spørreundersøkelse til skoler og skoleeiere høsten 2018. NIFU Rapport 2018:34.

Wendelborg, C.(2019). Analyser av indekser på Skoleporten 2018: Analyser på fylkes- og nasjonalt nivå for 7. trinn, 10. trinn og Vg1. Trondheim: NTNU Samfunnsforskning.

Ekspertgruppa om lærerrollen. (2016). Om Lærerrollen. Et kunnskapsgrunnlag. Oslo: Fagbokforlaget.

Pupil-to-teacher ratios and required qualifications

Almost 70,000 teachers are currently working in Norway. They are teaching 636,250 primary and lower secondary pupils. The main duties of a teacher are to plan, deliver and assess the pupils’ learning and to adapt the tuition to each pupil and the class as a whole. The social mandate given to teachers is to promote pupils’ learning and development (The expert panel on the role of the teacher, 2016).

New regulations and earmarked funding has increased teacher density

In the autumn of 2019 there were more than 40,300 full time employees (FTEs) dedicated to mainstream teaching in public schools. There has been an increase of 3,175 FTEs allocated to mainstream teaching since 2014 as a result of funding being earmarked for training more teachers in the past five years. The increase in teacher FTEs has resulted in an increase in the teacher density, and there are now 15.9 pupils per teacher in Years 1–10 overall. This is a clear improvement in teacher density compared with the past ten years. The improvement is particularly evident in Years 1–4, where the pupil-to-teacher ratio went from 16.2 to 14.0 pupils per teacher between 2014-15 and 2019-20.

In the 2019-20 academic year there are 14.0 pupils per teacher in Years 1–4.

The proportion of primary and lower secondary schools that meet the statutory requirement is lowest in Years 1–4 at 81 per cent. However, it is also Years 1–4 that have seen the greatest increase – 5 percentage points since 2018 – in the number of schools satisfying the requirement. Many schools only lack 0.5 FTE in order to achieve the statutory ratio.

Two teachers per class is more common than multiple classes per year group

8 in 10 school leaders who have received funding to reduce the pupil-to-teacher ratio say that the additional resources are primarily being used to introduce a second teacher to existing classes. Just over 4 in 10 also say that the teachers are used for intensive courses in Years 1–4 (Rogde et al., 2018).

School buildings and educational considerations may play a role when deciding whether to divide classes or deploy additional teaching resources to existing classes when such resources are made available.

Correlations between pupil-to-teacher ratio and pupil performance are difficult to identify

Although research does exist on the causal effect of lower pupil-to-teacher ratios on pupil performance, there is little consensus between the researchers. The results vary depending on year group, class, country and differences in class sizes. Several large research projects are underway to investigate these correlations further.

Many teachers do not hold the required qualifications to teach certain subjects

To gain permanent employment as a teacher in compulsory education, applicants must hold a teaching qualification or other approved qualification. 5.7 per cent of teachers do not meet this requirement.

They must also have obtained a certain number of ECTS credits in order to teach certain subjects.

Many of the teachers with an approved teaching qualification do not meet the qualifications requirement in the subjects they teach. The percentage is highest in English, where 39 per cent of teachers do not meet the qualifications requirement. In mathematics the figure is 27 per cent, while it is lowest in Norwegian at 19 per cent.

The percentage of teachers who fail to meet the qualifications requirement is especially high in English in Years 1–7. 40 per cent of these teachers do not have the required ECTS credits.

If all of the teachers who do not meet the qualifications requirement for teaching Norwegian, mathematics and English were to enrol in continuing education, it would require 22,581 places to be created for them. There has been a steady fall in the proportion of teachers who do not meet the qualifications requirement since 2015-16. The biggest drop has been at the lower secondary stage.

Most schools assign two teachers to a class rather than create smaller classes.

Qualification requirements

Teachers of Norwegian, mathematics, English, Sami and Norwegian Sign Language must have obtained 30 ECTS credits to teach at the primary stage and 60 credits to teach at the lower secondary stage. Those who graduated before 1 January 2014 have dispensation from these requirements until 1 August 2025.

Out-of-school-hours care

The local authority must provide out-of-school-hours care (known as SFO) before and after ordinary school hours for pupils in Years 1–4 and for pupils with special needs in Years 1–7. The arrangements should include care and supervision and offer the children opportunities for play, cultural and leisure activities.

Many pupils attend SFO, especially in the lower year groups

6 in 10 children in Years 1–4 attend SFO. Just over half of the children who attend SFO have been given a full-time place. SFO participation in Years 1–4 has been fairly stable in the past ten years. The older the children, the less likely they are to sign up for SFO. 82 per cent of Year 1 pupils attend SFO, while in Year 4 the figure is 31 per cent.

SFO participation varies between counties and municipalities. In Oslo 87 per cent of pupils in Years 1–4 have signed up, while the lowest participation rate is found in Nordland at 47 per cent.

6 in 10 children in Years 1–4 attend SFO.

Few national guidelines

There are few national guidelines in place for SFO, and the scope for local input is great. This results in considerable variations in terms of design and staffing levels, content and objectives.

An evaluation of the SFO scheme has found that local authorities and SFO workers place varying degrees of emphasis on play and learning (NTNU, 2018). The scheme is referred to as SFO in most municipalities, while in Oslo and Drammen it is known as Activity School (Aktivitetsskolen). The different designations reflect different approaches to content and structure, although an evaluation of the SFO scheme has found that the content can be the same in practice (NTNU, 2018).

Parents are largely satisfied with out-of-school-hours care

90 per cent of parents say their children enjoy going to SFO, and almost as many (88 per cent) agree that they have a good relationship with the SFO workers, according to figures from the Parent Survey (Wendelborg, 2019).

Large variations in the cost of an SFO place

The cost of attending SFO is determined locally. The cost of a full-time place varies from NOK 0 to more than NOK 3,000. Around 4 in 10 schools offer discounts with income-based rates and/or free places. While 1,473 schools offer a sibling discount, 691 schools say they do not.

SFO may charge for voluntary organised activities such as ski or chess instruction, for example. Many schools are working with voluntary organisations to create SFO content. The autumn of 2020 will see the introduction of a nationwide scheme for means-tested parent contributions.

Lower cost means higher participation rates

The higher the participation rate, the more important SFO becomes from an inclusion perspective. An evaluation has found that SFO is not widely used as a means of and arena for including minority language children (Caspersen et al., 2019).

Free part-time places or reduced parent contributions are used by several local authorities to make SFO available to more children. Drammen municipality offers free SFO places in the afternoons for all children from low income families, while Oslo offers free part-time places to all Year 1 pupils. Some Oslo schools also offer places to other year groups. Participation has increased in schools that offer free SFO, something which indicates that cost has an impact on attendance. 76 per cent of pupils in Years 1–4 in Oslo attended SFO in autumn 2015. By autumn 2019 the figure had increased to 89 per cent. At Furuset school attendance rates in Year 1 increased from 33 per cent in autumn 2015 to 93 per cent in autumn 2019.

Local discount schemes and free part-time places may be the two most important means of giving more children the opportunity to attend SFO, and they can help provide access to many children who would otherwise not have benefited from the provision.

Adult basic education

There are almost 14,000 adults in primary and lower secondary education in the 2019-20 academic year. This group includes both adults receiving mainstream primary or lower secondary education and adults receiving special needs support. 98 per cent of participants in mainstream primary or lower secondary education for adults are minority language speakers.

Learning outcomes

A number of sources provide information about learning outcomes. The most important are national tests, exam results, coursework grades and international studies.

Improved grades in lower secondary

The Year 10 cohort of 2018-19 achieved an average point score of 42. This is 0.2 points higher than the previous year. The average point score has increased gradually over time. The increase has been slightly bigger for girls than for boys, and girls now obtain 4.6 points more than boys on average. The introduction of assessments in optional subjects helped raise the average point score since the average score in optional subjects is higher than in other subjects.

The increase in average point scores alone cannot be used to determine whether pupils are performing better. Trends in national tests primarily show little change over time, although there are signs that the percentage of pupils performing at the lowest proficiency levels is falling. However, the national tests measure far fewer competence aims than does the average point score, the latter representing the pupil’s overall attainment level upon completing compulsory education.

There was a 2.9 point discrepancy between the counties with the highest and the lowest average point scores in 2018-19. Oslo saw the biggest average increase and had the highest average in the 2018-19 academic year with 43.3 points.

3,300 pupils have not obtained grades in more than half of their subjects and are therefore not given an average point score. This is equivalent to 5.3 per cent of all pupils.

Stable results in Year 5

In the autumn of 2019 a total of 60,000 Year 5 pupils sat the national tests in reading, numeracy and English.

In reading the percentages of pupils performing at the highest proficiency level (level 3) and at the lowest level (level 1) both fell slightly compared with 2016. The result is that the proportion of pupils performing at the middle level has increased by 4.9 percentage points.

Boys are catching up with girls in reading

Girls have outperformed boys by one or two scale points in reading since 2016. However, in autumn 2019 girls and boys performed at the same level in the reading test. In numeracy and English the difference between the genders remained the same as in 2018. On average, boys score two scale points higher than girls in numeracy and one scale point higher than girls in English.

Compared with 2018, the proportion of girls performing at the lowest proficiency level in reading increased by 2.4 percentage points, while the proportion of boys performing at the lowest level fell by 2.7 percentage points. The proportion of girls performing at the highest level fell by 3.3 percentage points in the same period.

The biggest difference between girls and boys can be found at the highest proficiency level in reading. 29.6 per cent of boys performed at the highest level. For girls the figure was 21.1 per cent.

Few changes in national test results in Years 8 and 9

There were no changes in average scale points in reading and numeracy in Years 8 and 9. In reading the proportion of pupils performing at the two lowest levels fell from 28 to 25 per cent in the period 2016 to 2019.

In English the proportion of pupils at the two lowest proficiency levels decreased from 28 per cent in 2014 to 26 per cent in 2019.

PISA shows a decline in Norwegian pupils’ reading performance

PISA 2018 reveals a pronounced decline in Norwegian pupils’ reading performance since 2015 to levels seen in previous PISA surveys. The results in mathematics are the same as in 2015, while in science there was a slight drop. Norwegian pupils are still performing at or above the OECD average in all three subject areas.

PISA shows that 15-year-old boys have significantly poorer reading skills than their female peers

For the first time Norwegian girls are performing significantly better than boys in all of the three subject areas – reading, mathematics and science. The gender differences are considerable in reading but minor in science and mathematics. In reading there are more boys than girls performing at a low proficiency level, and there are fewer boys than girls performing at a high level.

In Year 5 boys performed slightly better than girls in English and numeracy and at the same level as girls in reading.

Changing reading habits

PISA 2018 also asked the pupils about their reading habits. More than half of all pupils (51 per cent) say they do not read in their spare time. In 2009 the figure was 40 per cent. The amount of time pupils spend in front of their screens is increasing, meanwhile. Changes in Norwegian pupils’ reading habits are in line with the trends in other countries, but more Norwegian pupils than the OECD average say they only read when they have to.

The pupils’ backgrounds mean less in Norway than in most other countries

In Norway there is less of a link between the pupils’ home background and school performance than in most other countries. There is also little variation between schools compared with other countries. This suggests that Norwegian schools are broadly able to offer an equitable education to pupils from different backgrounds and that the vast majority of schools have pupils performing at different proficiency levels.

What is PISA?

PISA measures 15-year-olds’ abilities in reading, mathematics and science.

The survey also provides information about other factors such as learning environment and the impact of the pupils’ home background on the results.

The survey is conducted every three years. All three subject areas are included in every survey, but the main subject area alternates from survey to survey. The main subject area is subject to additional academic tests and questions. Reading is the main subject area in PISA 2018.

The survey is anonymous and based on a random selection of pupils. This means that PISA can provide information about Norwegian pupils generally but not about individual schools or pupils.

In 2018 around 600,000 15-year-olds from 79 countries participated in the survey. Some 5,800 15-year-olds from 250 Norwegian schools took part.

The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training has delegated responsibility for the practical organisation of the PISA study in Norway to the Department of Teacher Education and School Research at the University of Oslo

OECD oversees the PISA survey internationally.

Upper secondary education and training

Students who enrol in upper secondary education or training have completed 10 years of compulsory education. At the upper secondary stage, they are able to choose their study programme and subjects according to their interests and what they want to do later in life in terms of work or study.

All young people who have completed compulsory education have the right to upper secondary education or training. 98 per cent of all 16-year-olds enrol in upper secondary in the same year that they complete compulsory education. A total of 93 per cent of all 16 to 18-year-olds were enrolled in upper secondary education or training in the 2018-19 academic year (Statistics Norway, 2019). They are able to choose between 15 different study programmes. Entrants to upper secondary schools are fairly evenly split between vocational study programmes and general study programmes. There is also scope for switching programmes along the way.

A growing number of young people choose to become apprentices. There were more than 29,000 applications for apprenticeship places in 2018. 74 per cent of applicants had obtained an apprenticeship contract by the end of the year – the highest figure since the scheme was introduced.

Schools and students

In the 2018-19 academic year there were 415 upper secondary schools in Norway with an average of 454 students per school. 23 per cent of upper secondary schools are private, and they tend to be smaller than public schools.

More students attend private schools

A total of 8 per cent of students attend private schools. Public upper secondary schools have an average of 541 students, while the average in private schools is 160. 42 per cent of private upper secondary schools have fewer than 100 students. In the autumn of 2018 there were 95 approved private upper secondary schools in Norway. All bar one of them had been approved under the Independent Schools Act. The two most common categories for approval are elite sports and world view respectively. Around half of all independent upper secondary schools are approved based on one of these two categories.

Large numbers of private school students in Oslo and Hordaland

Almost 15,200 students were attending a private upper secondary school in autumn 2018. Around 12,200 of them were enrolled on general study programmes, while almost 3,000 were enrolled on vocational study programmes. There are significant differences between counties as to how many of their students attend private schools. The largest numbers can be seen in Oslo and Hordaland where a respective 16 and 15 per cent of students attend private upper secondary schools. In Finnmark fewer than 1 per cent of students attend private schools.

Growing number of adults in upper secondary education and training

Adults who have completed compulsory education but not upper secondary education or training are entitled to free upper secondary education or training.

There were 16,100 adults over the age of 25 enrolled in upper secondary schools or adult education centres in 2018-19. This is an increase of 16 per cent on the previous year. Almost 80 per cent of them are enrolled on training programmes specially designed for adults. Participant numbers have increased the most on the Healthcare, Childhood and Youth Development programme. Adult participants primarily take individual subjects in order to obtain general university and college admissions certification or they study Healthcare, Childhood and Youth Development. Almost 60 per cent of adult participants in 2018-19 were women.

Although women are in the majority, the biggest increase is amongst male participants. There are now 3,000 more male participants than five years ago, and the Building and Construction and the Technical and Industrial Production programmes have seen the biggest increases.

Study programmes and subjects

73,400 students started upper secondary level 1 (short form Level Vg1) in autumn 2018. More than half of them enrolled on a general study programme. Specialisation in General Studies is the biggest of all the study programmes, accounting for 38 per cent of all students at Level Vg1.

1 in 4 students on vocational programmes studies Healthcare, Childhood and Youth Development

Healthcare, Childhood and Youth Development is the largest of the vocational study programmes, accounting for more than a quarter of all vocational students in autumn 2018. The proportion of students studying Healthcare, Childhood and Youth Development has increased by more than 6 per cent in the past five years.

Technical and Industrial Production and Electrical and Electronic Engineering are the second and third largest programmes with a respective 17 and 13 per cent of all vocational students at Level Vg1.

Just over half of all students enrol on a general study programme at Level Vg1.

More boys are choosing Healthcare, Childhood and Youth Development

There are significant gender differences on the vocational study programmes in particular. However, Healthcare, Childhood and Youth Development has gradually become less female dominated over time. Between 2012-13 and 2018-19 the proportion of boys enrolled on this programme rose from 17 to 21 per cent. There has been little change on the male dominated study programmes. Boys made up a respective 95 and 94 per cent of students enrolled on the Building and Construction and the Electrical and Electronic Engineering programmes. This is only marginally lower than in 2012-13.

Languages, Social Sciences and Economics is the most popular general programme area

Of those enrolling on the Specialisation in General Studies programme at upper secondary level 2 (short form: Level Vg2), 55 per cent choose to specialise in Languages, Social Sciences and Economics, while 42 per cent choose Mathematics and Sciences. The remaining 3 per cent opt for programme areas only offered by certain private schools. The distribution of students across programme areas has remained relatively stable in recent years.

A growing number of boys choose to study Healthcare, Childhood and Youth Development.

Students and apprentices at Level Vg3

There were 51,200 students enrolled at Level Vg3 in autumn 2018. In addition to those were 43,300 apprentices, more than 1,800 trainees and 1,100 students receiving vocational training in school.

Many pursue Supplementary Studies after completing Level Vg2 of a vocational programme

Although almost half of all students at Level Vg1 enrol on a vocational study programme, a large number of them eventually obtain general university and college admissions certification.

51,200 students started Level Vg3 in autumn 2018. One fifth of them, 10,800, were students who had enrolled on a vocational study programme and were pursuing Level Vg3 Supplementary Studies to obtain general university and college admissions certification. 21 per cent of students on vocational study programmes choose Vg3 Supplementary Studies. Student numbers on general study programmes have changed little in the past few years.

3 in 4 find an apprenticeship

There were more than 29,000 applications for apprenticeship places in 2018. 21,700 of applicants obtained an apprenticeship place. This is 74 per cent of all applicants, the highest figure since records began in 2011.

There was a total of 43,300 apprentices in 2018. This figure includes both new apprentices and those who had been in apprenticeship for more than one year. In addition to those were more than 1,800 trainees and 1,100 students receiving vocational training in school. 72 per cent of apprentices are boys.

The number of apprentices has risen by 19 per cent since 2012, which is when the social partners and the Ministry of Education and Research signed the Social Contract committing them to work together to create more apprenticeships.

Most new apprentices in Building and Construction

Building and Construction saw the greatest influx of new apprentices in 2018. Healthcare, Childhood and Youth Development has had the biggest increase in new apprentices in recent years with 1,240 more apprentices than in 2012. The biggest decline has occurred in Design, Arts and Crafts with 178 fewer apprentices than in 2012.

Hairdressing is by far the largest programme area on the Design, Arts and Crafts programme with 73 per cent of all new apprentices. This programme area has seen a drop of 247 new apprentices since 2012, however. There has also been a decline in applications for Level Vg1 Design, Arts and Crafts in the same period.

3 in 4 find an apprenticeship.

The number of apprentices has risen by 19 per cent since 2012

Learning outcomes in upper secondary education and training

Improved coursework grades

Coursework grades have risen slightly in the past five years – by up to 0.3 points – in most common core subjects. The average coursework grade has also increased by up to 0.3 points in most programme subjects.

Students normally receive lower grades in their written exams than for their coursework, but there is little difference between coursework grades and oral exam grades.

Subject | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

English, Level Vg1 general study programmes |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.4 |

English, Level Vg2 vocational study programmes |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

Mathematics 1P-Y |

3.2 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

Mathematics 2P-Y |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

Mathematics 1T-Y |

3.6 |

3.7 |

3.9 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

Mathematics 1P |

3.3 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

Mathematics 1T |

3.9 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

Mathematics 2P |

3.4 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

Norwegian, Level Vg2 vocational study programmes |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

Norwegian (primary Norwegian language form), Level Vg3 general study programmes – written |

3.8 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

Norwegian (secondary Norwegian language form), Level Vg3 general study programmes – written |

3.6 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

Norwegian, Level Vg3 general study programmes – oral |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

Source: Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training | |||||

Girls get better grades than boys

Girls receive better grades than boys on average for their coursework and in both written and oral exams in most common core subjects. The smallest differences between boys and girls can be found in PE and Mathematics and the biggest in Norwegian, Social Sciences, and Religion and Ethics.

In the common core subjects boys only receive better average coursework grades than girls in PE and Applied Mathematics on the Supplementary Studies to Qualify for Higher Education programme.

Girls also get better grades than boys in most maths and science subjects. The smallest differences between girls and boys are in Chemistry, Physics and Information Technology.

9 in 10 pass their trade and journeyman examination

A total of 27,570 trade and journeyman’s examinations were completed in 2017-18. 61 per cent of those sitting the exams were apprentices and 34 per cent practice candidates. Only 5 per cent sat the examination as students after having completed vocational in-school training. 93 per cent of the completed exams were given a pass or pass with distinction.

There are relatively minor differences between counties and study programmes in terms of the proportion of candidates who pass the apprenticeship and journeyman’s examinations. The percentage receiving a pass or pass with distinction varies from 87 in Design, Arts and Crafts to 95 per cent in Technical and Industrial Production and Services and Transport. In terms of counties, the proportion of candidates who obtain a trade or journeyman’s certificate ranges from 88 per cent in Oslo to 96 per cent in Sogn og Fjordane, Telemark and Oppland.

Learning outcomes in upper secondary education

Exam results and coursework grades are a reflection of the students' attainment level upon completing a course of study. Grades from lower secondary school are mainly used for admission to upper secondary, while grades from upper secondary are primarily used to transition into work or for admission to higher education. There are no national tests in upper secondary education and training.

Sources

Kunnskapsdepartementet. (2019). Skolen må bli bedre til å løfte guttene! Pressemelding 04.02.2019.

Statistisk sentralbyrå. (2018). Dette er kvinner og menn i Norge 2018.

Statistisk sentralbyrå. (2019). Videregående opplæring og annen videregående utdanning.

Samordna opptak. (2019). Spesielle opptakskrav.

Cost of kindergarten provision and primary and secondary education

Every year local authorities and county councils spend large sums on education. In 2018 Norway spent almost NOK 156 billion on kindergartens and primary and lower secondary education.

Cost of kindergarten provision

Local authorities fund most (more than 80 per cent) of the cost of operating both municipal and private kindergartens. Around 15 per cent of the cost of running kindergartens is covered by parents, while public grants and other funding from local authorities and kindergarten owners make up a small part of the funding. Local authorities spent a total of NOK 46.4 billion on kindergartens in 2018, an increase of more than 2.2 per cent since 2017. This figure includes the cost of running municipal kindergartens as well as grants given to private kindergartens, but it excludes parent contributions (KOSTRA 2019). 14.4 per cent of all local authority spending went on kindergartens in 2018. The level of spending varies between 3 and 25 per cent from municipality to municipality.

In 2018 local authorities spent an average of NOK 124,200 on each child with a full-time kindergarten place (KOSTRA, 2019). The figure includes local authority grants given to private kindergartens but excludes government grants and parent contributions. The sum ranges from NOK 101,637 to more NOK 245,000 per child. Most children – 98 per cent – attend kindergartens where the local authority spends between NOK 100,000 and 140,000 per child.

Local authorities spent a total of NOK 21.2 billion on private kindergarten grants in 2018. The grants account for 46 per cent of local authorities’ overall spending on kindergartens.

A total of 33,459 households benefited from reduced parent contributions due to low income in 2018, and local authorities spent NOK 644 million on the discount scheme. This is NOK 146 million more than in 2017.

Parent contributions and discount schemes

Discount schemes are in place to ensure that children from families on low incomes can attend kindergarten. No one should pay more than 6 per cent of their income in kindergarten fees. In 2018 this scheme applied to families with a combined income of less than NOK 533,500. Families with an income of less than NOK 450,000 are also entitled to 20 hours of free kindergarten time per week

With effect from August 2019 the income limit was increased to NOK 548,500 and the entitlement to free core time extended to also include 2-year-olds.

A child in kindergarten costs an average of NOK 124,200.

Cost of compulsory education

In 2018 local authorities spent NOK 73.9 billion on municipal primary and lower secondary schools (KOSTRA, 2019). On top of that came the cost of out-of-school-hours care (SFO) at NOK 1.4 billion. The government also provides NOK 2.5 billion in grants to primary and lower secondary schools approved under the Independent Schools Act.

A pupil in a municipal primary or lower secondary school cost an average of NOK 121,200 per annum in 2018 (KOSTRA, 2019). NOK 98,000 of that figure went on teachers, school materials and similar, while NOK 23,000 was spent on premises and school transport (Figure 4.5). The total cost per pupil increased by almost 2 per cent, equivalent to NOK 2,270 per pupil, between 2017 and 2018.

Expenditure varies greatly from local authority to local authority. 37 per cent of local authorities spend between NOK 100,000 and 130,000 per pupil. 79 per cent of pupils live in these municipalities. 62 per cent of municipalities spend more than NOK 130,000 per pupil. 19 per cent of pupils live in these municipalities.

Cost of upper secondary education and training

In 2018 county councils spent NOK 29 billion on upper secondary classroom education and NOK 3.6 billion on vocational training in the workplace. The cost of vocational training in the workplace rose by 6 per cent. This was due to both more apprentices being trained and increased funding. The government also spent NOK 1.6 billion on grants for independent upper secondary schools. County councils spent almost NOK 591 million on upper secondary provision specially adapted for adults.

A student in upper secondary costs more than a pupil in primary or lower secondary

County councils spend an average of NOK 165,100 per student in upper secondary education. The figure includes the cost of national courses, special needs education and the educational psychology service (PPT). That is just over NOK 44,000 more than the cost per primary and lower secondary school pupil. Not including national courses, special needs education and the educational psychology service, a student enrolled on a vocational study programme costs NOK 27,000 more on average than a student on a general study programme, largely due to smaller classes and more expensive study materials.

Expenditure varies greatly between the different study programmes. The average study programme costs NOK 100,000 per student. The most expensive programme – Agriculture, Fishing and Forestry – costs almost NOK 157,000 per student, while the Specialisation in General Studies programme costs NOK 67,400 per student.

School environment and well-being

All pupils and students are entitled to a safe and good school environment that promotes health, well-being and learning. The vast majority of pupils enjoy going to school and benefit from a good learning environment. There has been a slight drop in the number of pupils being bullied at school. However, there has been an increase in the proportion of pupils who feel that they are being excluded socially and that they do not feel they fit in at school.

Well-being and sense of belonging

The majority of pupils – 88 per cent – are happy or very happy at school. 9 per cent state that they are slightly happy and 3 per cent that they are not happy at school. These results relate to pupils from Year 5 in primary school to Level Vg3 in upper secondary. A consistently high level of well-being can be seen in every year except Years 9 and 10, where reported well-being is slightly lower (Student Survey 2018: Wendelborg et al. 2019). The proportion of pupils enjoying school increases with their parents’ socio-economic status (Bakken 2019).

Boys and girls are equally happy at school

Boys and girls are equally happy at school (Wendelborg et al. 2019). Figures from Ungdata show that girls previously enjoyed lower and upper secondary more than boys, but this gap has now been closed. Looking at figures from 2011, boys’ well-being has remained virtually unchanged, while girls have seen a slight decline in well-being (Bakken 2019).

Most pupils have friends and feel that they fit in at school

The feeling of fitting in and having friends is important to be able enjoy school. The PISA survey shows that most 15-year-olds in Norway feel a sense of belonging and have friends at school (Jensen et al. 2019).

The proportion of pupils who positively state that they feel they belong, make friends easily and feel that they are liked by their peers fell by between 8 and 9 percentage points between 2003 and 2018. In the same period there was an increase in the percentage of pupils who gave affirmative answers to negative statements about being left out, feeling lonely and not fitting in. The increase was between 6 and 9 percentage points between 2003 and 2018 (Jensen et al. 2009).

The Norwegian survey Ungdata shows that young people spend less and less time going out with friends. While four in ten lower secondary pupils spent time with friends at least two evenings a week in 2012, only three in ten did so in 2015 and 2018 (Bakken 2019).

A large proportion of young people feel bored and stressed at school

Despite consistently high levels of well-being, 70 per cent of all lower and upper secondary pupils feel bored at school. Relatively many of them also feel stressed at school, especially girls. 6 in 10 girls and 3 in 10 boys say they often or very often feel stressed by their schoolwork. The feeling of stress is highest in Year 10 and at Level Vg3 (Bakken 2019).

Order in the classroom

Norwegian classrooms have become more orderly. According to teachers, lessons are quicker to get started, there were fewer interruptions from pupils and slightly less disruptive noise in 2018 compared with 2008 and 2013 (Throndsen et al. 2019).

Pupils are also reporting better order in class. 63 per cent of the respondents to the Student Survey say they agree or strongly agree that there is order in class. The figures are slightly lower in Years 9 and 10 than in other year groups. Responses to this question remained largely unchanged between 2016 and 2018 (Wendelborg et al. 2019).

The PISA survey corroborates these findings. Fewer pupils experienced noise and disorder in 2018 compared with 2000 and 2009. The survey only asked about orderliness in Norwegian lessons in these three years. Pupils in the average of OECD countries are also reporting slightly better order in class in PISA 2018 compared with 2009, although the improvement is not quite as big as for Norwegian pupils (Jensen et al. 2019).

The Student Survey and PISA differ in who is being asked and how the questions about order in the classroom are phrased. PISA asks about noise and disorder, and it only asks 15-year-olds about it in Norwegian lessons. The Student Survey asks pupils and students from Year 5 to Level Vg3 about order in class for all lessons.

There is less noise and disorder in Norwegian classrooms.

Bullying

The Student Survey defines bullying as repeated negative actions by one or more people against a pupil who may find it difficult to defend themselves. Bullying could mean calling someone names and teasing them, excluding someone, gossiping or hitting, pushing and holding.

6.1 per cent of pupils have been bullied

In 2018 6.1 per cent of pupils say they are being bullied at school either online or in other ways at least 2–3 times a month. In 2017 the figure was 6.6 per cent. 1 per cent of pupils say they have only been bullied online, while 0.9 per cent state that they have been bullied both online and in other ways while at school (Wendelborg et al. 2019).

Bullying in school mostly involves being called names or teased in a way that is hurtful – 66 per cent of pupils who are being bullied give these two examples. 46 per cent of pupils who have been bullied were excluded and gossiped about, while 24 per cent have been physically bullied (Wendelborg 2019).

Cyberbullying is much the same as other forms of bullying but without the physical aspects. It can take place in chats between certain pupils where the victim is not present. Pupils who experience cyberbullying are often also worried about the spread of pictures and negative descriptions, and they do not always know who is behind the bullying. The problem with cyberbullying is that it takes place both at and outside school (Wendelborg et al. 2019).

Decline in bullying in older year groups

9.2 per cent of Year 5 pupils are being bullied at school and/or online. This figure drops as the children get older before increasing slightly again in Year 9 and 10 and then declining. 3.2 per cent of students at Level Vg3 are being bullied.

County governors are receiving a growing number of bullying complaints

16 per cent of pupils in 2018 said their school knew about the bullying but did nothing. 37 per cent of pupils who were being bullied said that no adults knew about the bullying (Wendelborg et al. 2019).

A growing number of bullying cases are being reported to the county governors. By the autumn of 2018 a total of 653 complaints had been submitted to the county governors, a slight increase on the 565 cases in 2017.

Absence

A poor school and learning environment may have adverse consequences for the pupils, and for some it may lead to truancy and/or school refusal. Schools often place absences from school in two different categories: authorised and unauthorised absenteeism. Authorised absenteeism is absenteeism for valid reasons such as illness or approved leave (Havik 2018).

For some pupils absence can result in a vicious circle that is difficult to break out of. where frequent absence often leads to more absence. The more complex the absence pattern of the pupil, the higher the prevalence of anxiety, depression and stress (Havik 2018). Consistency and a good relationship between teacher and pupil are therefore important in order to prevent school refusal (Havik 2018).

High levels of absence in Year 10

A Year 10 pupil is typically absent from school for 6 days and 5 school hours. There were few changes in absence levels from 2014-15 to 2018-19. Pupils in Year 10 are absent for 3 days more but 6 school hours fewer than students at upper secondary level Vg1. Pupils of parents with only compulsory education are more often absent in Year 10 than pupils of parents with upper secondary or higher qualifications (Utdanningsdirektoratet 2019a).

More pupils are playing truant

Almost 1 in 4 pupils in lower secondary has played truant, according to Ungdata. In upper secondary the figure is 11.2 per cent. The percentage increases year on year from 19 per cent in Year 8 to 48 per cent at Level Vg3. Truancy levels amongst boys and girls are fairly similar. The majority of pupils who play truant do so between one and five times. The proportion of pupils who have played truant more than five times stands at 4 per cent in lower secondary and 9 per cent in upper secondary (Bakken 2019).

The proportion of pupils who play truant in lower secondary increased significantly from around 20 per cent in 2015 to around 25 per cent in 2018. The figures for upper secondary show a reverse trend with a drop between 2015 and 2017. The drop may be linked to new rules on absenteeism in upper secondary. There was also a slight increase between 2017 and 2018 (Bakken 2019).

Absence limit has reduced absenteeism in upper secondary

An upper secondary student is typically absent from school for 3 days and 11 school hours. This is 3 days fewer than in primary and lower secondary, but 6 school hours more.

Unlike lower secondary, there is an absence limit in upper secondary education. The limit was introduced in autumn 2016.

The number of days and hours missed fell considerably when the limit was introduced, and the number of days missed remains low and stable. The number of school hours missed has increased from 10 to 11 for all three upper secondary levels combined, however (Utdanningsdirektoratet 2019a). The number of hours missed is highest at Level Vg3 at 15 hours both before and after the absence limit was introduced.

A Year 10 pupil is typically absent from school for 6 days and 5 school hours.

Higher completion rates amongst students with little absence in lower secondary

There is a correlation between few absences in lower secondary education and completion rates in upper secondary education and training. Students who had completed upper secondary within five years in 2018 had had few days off on average in Year 10 (Statistics Norway 2018).

The absence limit has an adverse impact on some students

Although overall absenteeism has fallen since the absence limit was introduced, a group of students are at risk of being forced out of upper secondary education and training because of it. They are students who are already frequently absent and now struggle even more to complete upper secondary (Bjørnset et al. 2018).

Students who have exceeded the unauthorised absence limit or whose work cannot be assessed, e.g. because they have failed to turn up to important exams, will be marked NA (no basis for assessment) instead of receiving a numeric grade. There was a slight increase between 2017-18 and 2018-19 in the percentage of students whose coursework was marked NA. The proportion of students who received an NA in at least one subject increased from 3.0 to 3.2 per cent on average. A total of 5,351 students received an NA in the 2018-19 academic year. Just under half of them received an NA in just one subject.

Sources

Bakken, A. (2019). Ungdata 2019. NOVA. OsloMet.

Bjørnset M., Drange, N., Gjefsen, H., Kindt, M. T & Rogstad, J. (2018). I fraværsgrensens dødvinkel. Evaluering av fraværsgrensen i videregående opplæring. Delrapport 2. Fafo-rapport 2018:41.

Havik, T. (2018). Skolefravær. Å forstå og håndtere skolefravær og skolevegring. Gyldendal Akademisk.

Jensen, F., Pettersen, A., Frønes T.S., Kjærnsli M., Rohatgi A., Eriksen, A. og Eva K. Narvhus (2019). PISA 2018. Norske elevers kompetanse i lesing, matematikk og naturfag. Universitetsforlaget.

Kjærnsli, M. og Jensen, F. (2016). Stø kurs. Norske elevers kompetanse i naturfag, matematikk og lesing i PISA 2015. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Kunnskapsdepartementet. (2019). 653 mobbesaker til fylkesmennene i fjor høst. Pressemelding 22.01.2019.

Pellegrini, D. W. (2007). School Non-attendance: Definitions, meanings, responses, interventions. Educational Psychology in Practice, 23(1), 63-77.

Statistisk sentralbyrå. (2018). Karakterer og grunnskolefravær kan påvirke fraværet i videregående.

Throndsen I., Carsten, T. C. & Bjørnsson, J. K. (2019). TALIS 2018. Første hovedfunn fra ungdomstrinnet. ILS, NIFU.

Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2019a). Fravær på 10. trinn for skoleåret 2018-19.

Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2019b). Fravær i videregående skole skoleåret 2018-19.

Wendelborg, C. (2019). Mobbing og arbeidsro i skolen. Analyse av Elevundersøkelsen skoleåret 2018/19. Trondheim: NTNU Samfunnsforskning.

Pressemelding NTB Kommunikasjon. (2018). Elevundersøkelsen 2018 - færre elever sier de blir mobbet.

Wendelborg, C., Røe, M., Buland, T. & Hygen, B. (2019). Elevundersøkelsen 2018. Analyse av Elevundersøkelsen og Foreldreundersøkelsen. Trondheim: NTNU Samfunnsforskning.

Special educational support and special needs education